A role model of mine died a couple years ago, but I did not realize it until after he was gone.

I heard the news of Bob Raiford’s passing from an old friend who, like me, used to listen to his commentary pieces on The Big Show, a syndicated radio program out of Charlotte. It aired on classic rock stations, which is how my buddies and I came to know and love Raiford.

Since none of us ran with the cool crowd, we were mercifully spared from the popular music of our high school years in the late 1990s. Instead, we preferred the music our parents grew up with, especially the Southern rock classics we blared from my Chevrolet sedan as we drove the back roads of Central Florida.

Our parents’ old record players had long since broken down and we didn’t want to spend our money on CDs, so classic rock was mediated to us by WHTQ 96.5-FM out of Orlando. As a consequence, we along with millions of morning commuters all over the South and beyond, received a steady diet of The John Boy and Billy Big Show.

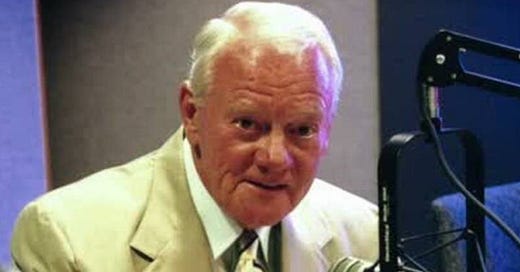

The programming was fun but not especially varied: News, jokes, and occasional interviews interspersed with the affiliate station’s news, weather, traffic, and ads. John Boy laughed too much and too loud. Billy seemed too much like a dad. But Raiford dazzled us boys. He was old (so we thought, although he was only in his late 60s at the time) and he was irreverent. There was just something about him that really impressed me. And so I determined to make a personal connection.

During my senior year, our class president moved out of state. This left a power vacuum in which the details of our graduation ceremony would be up for grabs. A group of popular girls had commandeered the process, and we didn’t like it. I can’t remember what crappy tune they voted to be our class song, but we weren’t going to let those girls take over graduation.

It would be on the question of commencement speaker that my group would wage its battle. My friend Brad, the one who notified me of Raiford’s death at age 87 last fall, nominated Goose Givens, a 1970s University of Kentucky basketball star who had done color commentary for the Orlando Magic since the team’s inception in 1989.

But something urged me to think bigger. Maybe it was my mom, who reminded me that her Class of 1974 heard a speech by Connie Chung, an up-and-coming news broadcaster in Atlanta who went on to national fame as an anchor for CBS.

Could the Class of 1999 do even better? It was an era of thinking big. This new thing called the Internet was going to make the world smaller. We were going to get out of that little town anyway. Why should we hear from an Orlando person? I instantly thought of Raiford.

As luck would have it, he was in the area. I don’t remember if it was just for some kind of Big Show promo tour or if there was a launch at the Space Center that weekend. But in any case, Robert D. Raiford was in Orlando, just 15 miles from where we sat in that graduation planning meeting. So we determined to meet him. This did not impress the class steering-committee girls, but we never impressed them anyway.

It must have been the weekend of the Daytona 500. The Big Show crew had a race-themed event at a shopping and dining venue in Orlando’s tourist corridor. When we arrived, John Boy was laughing loudly, per usual. Billy was more animated in person than I would have assumed. Everyone was having a good time, but we could not find the man we came to see.

I heard him before I saw him. The old broadcaster’s voice was unmistakable. Our hero was, as he might have said, half-full of corn liquor, and not nearly as lucid as as when he was reading his type-written essays on the radio. But through the music and the crowd, we got our message across: We are high school seniors in the next town down from here, and we want you to be our commencement speaker in May. “Write me a letter,” Raiford said.

And so I did.

I already figured I had a knack for epistolary eloquence. When I was 13, I sent a letter to the superintendent about how boring and pointless school was. This prompted a personal call to my father, who, in turn, gave me a talking-to I wouldn’t soon forget.

But Raiford’s influence was already upon me, even as I sat at our big, boxy family computer and typed into a primitive version of Microsoft Word. Earlier that winter, our college applications were due. The school’s guidance counselor said the application essays should be creative. But I was not a creative kid. I was, however, at least an average essay writer, having managed to make good grades in English in the days before literature and composition were cast aside to fill the curriculum with preparation for state standardized tests. So my solution to the college-application essay dilemma was simple: I formatted my essay like a newspaper column, printed it out on legal-size paper, and sent it off. (It was good enough for Emory, Vanderbilt, and Wake Forest, but not Duke. Anyway, I ended up at Oklahoma Baptist University. Long story.)

My affinity for the written word ran even deeper than I realized. I read the Bible, and was secretly more astonished by its literary beauty than its theological coherence. I read the daily paper every morning after my dad was finished with it. I guess I thought every kid read the Bible, and every kid read the newspaper after his dad was finished with it, and every kid grew up with is dad in the house. It was not until much later that I realized my traditional upbringing was no longer the norm in America — even in the South — if it ever was at all.

We were not high-culture people, at least I didn’t think so at the time. But my parents read books, and sometimes I read them, too. My dad especially loved Miami’s Dave Barry and the late Atlanta columnist Lewis Grizzard. I loved them, too. We went to church on Sundays and, being religious but not spiritual, I cherished the way humans throughout the ages attached words to their longings for God in Scripture, songs, and sermons. Word and Sacrament, they said. I liked the word part just fine, but didn’t like Communion on the first Sunday of each month because it cut into the hymns and readings and sermon.

We had a family friend in the newspaper business, but I didn’t know any writers except a lady in our church who wrote occasional pieces about fishing in the local paper. We didn’t subscribe to The Atlantic Monthly or The New Yorker. But I read Tom Verducci’s essays in Sports Illustrated.

I dabbled a lot in music and sports as a kid, but wasn’t very good at either. I was, however, pretty good with words. I only wish I had done more to nurture my ability then. Instead, I waited 15 years after graduation before I got paid to write anything.

A week or so after I mailed my letter to Raiford in Charlotte, I arrived at school one morning to a great commotion that I had unknowingly caused. For some reason, I had not listened to The Big Show that morning. But Robert D. Raiford read my letter on the air and accepted my invitation to address the Osceola High School Class of 1999 at our graduation. As with most big moments of my youth, I had done something that adults around me found impressive but few kids my own age cared about. Still, it was fun in a nerdy kind of way to be the man of the hour.

As it turned out, there was to be a space shuttle launch at Cape Canaveral the day before or after our ceremony. Raiford was going to make a little trip out of it. My buddy Brad’s uncle lived across the street from him and had a drunk friend who would come around but never paid much attention to us boys playing basketball in the street between the two houses. But suddenly I was a hero to this fella, who begged for me to bring the legendary Robert D. Raiford to hang out on his back porch. “Raiford would like the back porch,” Charley confidently predicted.

Raiford probably would have liked the back porch. But at the time, I gave little thought or notice to the fact that the only people excited about Raiford were old, white, redneck, or, likelier, some combination of the three. The black and Hispanic kids in my senior class seemed unimpressed by what I had achieved, even as more than a few older family friends thought it was pretty damn cool.

So who was this aging newsman, Raiford? The truth was, I didn’t know. I just knew I liked him and I liked the style and content of his radio commentaries on the John Boy and Billy Show. Raiford was direct and said what was on his mind. I was verbose yet always timid with my words, always worried what people would think or say. Raiford railed against political correctness. It would take me over a decade to get up the courage to call out P.C. B.S. when I saw it. Raiford had a keen sense of right and wrong, yet came across as more principled than moralistic. This struck me as enviable. I either lack principles or are often indifferent to them, and I wallow in epistemic anguish over morality to this day. It’s kind of my personal brand.

Raiford was a radio man in the television era. He was old fashioned in a good way, something I try, and fail, to be all the time. Raiford wrote on a typewriter. I type my words into an unknowable array of folders and files whose names I can barely remember but that, for better or worse, sync seamlessly across all my devices. I know in my heart I would write more and more joyfully if I used a pen and notepad while smoking a pipe and listening to the radio in my front porch chair. But my iPad has baseball scores and Twitter updates.

Outside the Big Show audience, Americans knew Raiford from President Kenney’s funeral, if they knew him at all. He was a young reporter for WTOP, then and now a premier drive-time news station in Washington. On the morning when JFK’s horse-drawn casket traveled down Pennsylvania Avenue, WTOP’s Bob Raiford provided audio for a national audience.

But Raiford had a noteworthy career before and after. In the 1950s, he stood up to station managers in the South who forbade him from expressing his liberal civil-rights views on the air. In middle age, Raiford had a series of broadcast jobs and shows. But the Big Show was his claim to fame.

All this was acknowledged as our principal introduced Raiford before he gave his commencement address. Since I was the one responsible for all this, I had been allowed to be on the stage for that portion of the ceremony. I sat in Raiford’s seat on the platform while he stood and delivered the speech. I actually don’t remember much about the address at all, except that at one point our principal leaned over to me and whispered in my ear, “Am I going to have look for a new job after this?” I think Raiford had made a judgmental remark about unwed teenage mothers, of which we had a few in our graduating class. The only direct quote I recall from the speech is, “I didn’t fail high school. High school failed me!” I don’t think he was half-full of corn liquor. But I wouldn’t swear to it.

Before I knew it, Raiford’s speech had ended. Just like high school ended. Just like my childhood ended. Life went on. Some of us moved away, while some of us stayed. Some of us, like me, moved away away and then came back and then left again. I still like Southern rock and love my old buddies like brothers, even though we rarely get together — and by rarely I mean pretty much never. But I didn’t think of Robert D. Raiford again until he died, at which point I immediately realized how much my life had unfolded under his influence.

In a sense, Raiford was what I wanted to be, if I could ever admit to myself and others and if “curmudgeon-at-large” was actually a job I could get. But eventually I did find my way into writing professionally. This was after I had abandoned the orthodoxies of the Right, and then of the Left, and declared my willingness to commit Thought Crimes. It’s a lot easier to get paid when you are spouting a party line, but so far I have happily settled for less and maintained my integrity — as a writer anyway — in ways I think Raiford would approve of. Now when readers say I’m independent or old-fashioned or curmudgeonly, I think about how all those Raiford segments on John Boy and Billy’s morning radio show formed me into the writer I am today.